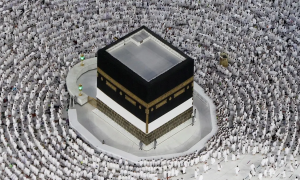

With an estimated 1.8 billion Muslims, or nearly a quarter of the world’s population, there are Muslim communities in practically every continent. Despite the diversity of these societies’ cultures, languages, and customs, they all have a similar sense of spirituality and a set of principles that direct their behaviour and interactions with other people.

A variety of factors, such as political, economic, and social circumstances as well as world events like the emergence of extreme ideologies, the War on Terror, and the COVID-19 epidemic, have an impact on the contemporary state of Muslim communities around the world. In spite of these difficulties, Muslim communities have made and continue to make important contributions to modern society in fields including science, technology, literature, art, and activism. The depth and breadth of Islam’s cultural heritage, as well as its emphasis on wisdom, justice, and compassion, are reflected in these contributions.

The current situation of Muslim communities around the world will be examined, as well as their contributions to modern civilization and the opportunities and problems they face in the twenty-first century. The methods in which these communities are navigating complicated global dynamics and the part they play in determining the course of our interconnected globe will also be looked at.

Muslims in contemporary world

Violence in the Middle East and South Asia, two areas that are inextricably linked to Islam and Muslims, is a topic that is discussed in nearly daily news reports and media commentary. Muslims appear to be sliding into a cycle of violent nihilism as hopes fade in the wake of the Arab Spring and vile ISIS militants continue to wreak horror everywhere they control. Islam today seems to be nothing more than a wasted force that cannot replenish itself.

This is a story with a lot of staying power because the Western media is so prevalent and constantly promotes these ideas. The journalistic bar for news reporting is typically quite low when covering Muslim-majority cultures; sensationalism is a crucial criterion. Nearly all of what happens in regular people’s daily lives remains hidden. Little consideration is given to the vast spiritual and intellectual resources present within the Islamic legacy (both as a religion and civilisation), as well as the diversity of voices and ideas that continue to characterise communities with a majority of Muslims.

Contrary to common assumption, Muslims are fully integrated into the modern world and are coping with its many difficulties in a variety of ways. Many of them are re-engaging with their tradition and revisiting their past, just like many non-Muslims are doing with their individual traditions and histories in comparable situations, while navigating the sometimes unfamiliar waters of modernity with ingenuity and inventiveness. Modernity (or, more precisely, modernities) is shaping and being moulded by hermeneutic and revivalist efforts that are being led by Muslim academics, philosophers, and social activists. These projects are typically taking place underneath the global radar. Because there are various definitions of modernity, each tied to a society’s own historical trajectory and cultural peculiarities. Understanding how diverse roads to modernity can and are taken by distinct societies is essential. The secular modernity paradigm of the West is rarely a universal one in this context. Instead, it is a narrow model that developed as a result of particular historical occurrences in the past of Europe. A variety of nations and cultures are “indigenizing” modernity in ways that are consistent with their sociocultural institutions, lived experiences, and recorded history.

Muslim’s contribution to Contemporary world

Muslim men and women, like everyone else, are actively negotiating modernity, and they frequently demand (contrary to strong external pressure) that they do so on their own terms. Many of them are revisiting their religious books in an effort to find guidance in the negotiation process; they believe that religion is an ally, not an adversary, of the modern world. This approach occasionally involves challenging particular Sharia-style rules of traditional Islamic law. Laws that are the result of human reasonable reasoning cannot be equated with the Sharia. The Sharia is the repository of timeless, universal rules that push people to be the best versions of themselves; these rules must be understood and reinterpreted over time to allow for human development.

Islamic Feminism

This re-engagement with the Sharia and its central text, the Qur’an, which Muslims believe to be the account of God’s final revelation to humanity, has had an impact on Islamic feminism. Muslim scholars are analysing the Qur’an holistically and contesting some of the historically-bound, culturally-inflected, and gender-discriminatory laws that many male jurists devised during the pre-modern era. These contemporary academics are laying the groundwork for gender equality and female social empowerment in the Qur’an, ideas that are sure to find resonance in communities with a Muslim majority.One such society is Malaysia, where female activists from the Musawa (equality) organisation have already made a significant impact through their rereadings of crucial verses from the Qur’an that convincingly challenge gender injustice. Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan is a notable exception. Muslim women thinkers and social reformers are transforming their countries in a multitude of ways that frequently go unnoticed in the international press.

Democracy

Societies with a majority of Muslims are also experimenting with democracy, oftentimes against formidable obstacles. They will not allow this since there are aggressive obscurantism forces in their midst. They should be satisfied with the caliphate, especially as a counterbalance to democracy, which is after all a foreign invention. However, survey after poll firmly demonstrates that Muslims prefer accountable, representative governments that they elect themselves at the polls. All of this is thought to be in accordance with Sharia principles, which demand the use of consultation procedures (shura) in administrative matters. Therefore, it is unmistakably established that the majority of Muslims desire democracy and Sharia, both of which they believe were embodied in the first caliphate of the four Rightly-Guided monarchs that emerged in the centuries following the passing of the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century. Therefore, there is a fundamental explanation for why mainstream Muslims mock ISIS when it declares its fictitious caliphate. They recall the Rightly-Guided caliphate as being founded on justice, law, and order that the populace approved of—exactly the opposite of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s fictitious caliphate. Most Muslims are aware that Graeme Wood and other journalists are mistaking the seeming artefacts of Islamic history for Islam itself. It is not a genealogy of organisations with the same names that are devoid of such moral content, but rather a genealogy of ethics and morals that links them to their devout ancestors.

Jihad

And what about jihad, the most terrifying phrase that most Westerners associate with violent crime? Once more, ancient history and its sources save the day. The Qur’an contains numerous elements of jihad (battle; struggling), the most crucial of which is sabr, or patient patience, which must be consistently practised in the midst of life’s vicissitudes. Jihad also involves qital, or acting in self-defence against an aggressor who rejects diplomatic efforts. Considering how many extremists and the media portray jihad, one could be excused for believing that it entails killing non-Muslims because they obstinately refuse to convert to Islam. Such simplified narratives exclude the internal conflicts that have developed over time inside Muslim communities, particularly as they strive to establish the proper bounds of the military jihad. The concept that ultimately calls for Muslims to work to uphold what is good and right and to avoid wrongdoing without harming others is tarnished by such narratives as a result.

Stance against terrorism

Last but not least, the discussions that some Muslims have with some of the non-Muslim residents of the global village in which they live are never featured on the main page of our major publications. However, awareness of such interfaith and intercultural encounters helps refute the “clash of civilizations” concept, which is based on the idea that a reified Islam and a reified West are inherently antagonistic to one another. The “clash” theory holds that militant Islamist groups that are hostile to Westerners and right-wing Westerners are mirror images of one another. The terror-stricken world we live in today is proof that the hate-mongering of these organisations has caused immeasurable harm. However, strong-willed people of good will who have unwavering faith in the fundamental goodness of people attempt to rise above the fray and open lines of dialogue that support the development of shared ground and interreligious cooperation. Interfaith organisations in the US have confronted racists who attempted to thwart the establishment of the Park 51 Community Centre in New York. A Muslim-Christian alliance in Egypt resisted extremists when they targeted churches owned by the country’s minority Copts. Such interactions inspire optimism and develop a different story that emphasises shared values and objectives, ultimately discrediting the idea that a clash of civilizations is unavoidable.

Read More: The History of Islamic Finance and its Importance in the Global Economy – About Pakistan

Conclusion

In conclusion, a variety of political, economic, and social variables, as well as world events that have had a substantial impact on their lives and experiences, all contribute to the current situation of Muslim communities around the world. Muslim communities continue to make significant contributions to modern society in fields including science, technology, art, literature, and social activity despite the difficulties they confront.

The effects of poverty, conflict, and climate change are some of the key issues that Muslim communities deal with concurrently. Other issues include marginalisation, violence, and prejudice. Promoting intercultural and interreligious communication as well as working towards a more inclusive and equitable global society that respects and celebrates variety will be crucial in order to overcome these obstacles.

It will be crucial going ahead to acknowledge and support the excellent contributions made by Muslim communities, while also working to alleviate the difficulties they experience and encourage improved understanding and coexistence between many cultures and faiths. By doing this, regardless of a person’s faith, culture, or origin, we can create a more tranquil, just, and sustainable society for everyone.